Abstract: This blog includes the results of two general election analyses of studies conducted during the primary elections in 2020: the “postcard postmark” study and the “two primaries” study. In both of those primary studies, we found that voters who received GOTV postcards had statistically significantly higher odds of voting in the primary than people who didn’t receive GOTV postcards. Because we wanted to see if those effects traveled downstream to the general election, we matched the original study data back to the voter file to determine if people who received our primary GOTV postcards had higher odds of voting in the November general election. We found no significant downstream effects in either study, but there was some suggestive evidence that people who received postcards in the two primaries study voted at higher rates in the general election than control participants in that study. Further, there was a statistically significant interaction finding: receiving primary GOTV postcards was associated with higher odds of voting in the general election for people who already had high voter propensity scores, whereas they were associated with lower odds of voting in the general election among lower propensity voters.

Objective: This analysis explores the general election voting behavior of voters who SDAN sent GOTV postcards to ahead of the 2020 primaries, to determine if the increase in voter turnout we observed in those studies traveled downstream to increase turnout among those voters in the November 2020 general election.

Background: SDAN ran two postcarding studies during the 2020 primaries. In the postcard postmark study, participants were sent one postcard ahead of the primary election in North Carolina and Texas, with the postmark on the card either from in- or out-of-state. In the two primaries study, participants were sent one postcard ahead of each of the two primary elections in Florida and Minnesota (voters in Georgia also received primary postcards but these data were removed from the analysis due to pandemic election issues in Georgia). Both studies found that postcards provided a significant boost to primary voter turnout, in the range of 1.25-2.17%. This analysis seeks to determine if this primary GOTV tactic continued to influence voters through the general election months later.

Specifics:

Postcard postmark – The sample included randomly chosen voters from competitive state legislative districts in Texas and North Carolina who were considered Democratic base voters (partisanship scores of 80+) but low-mid voter turnout propensity (25-60). After pulling all voters who fit this criteria, we randomly selected 15,000 voters from each state’s list, and randomized them into the 3 conditions: control (no postcard), in-state postmark, and out of state postmark. This resulted in a sample size of 30,000. Sister District volunteers wrote the GOTV postcards and mailed them either to an in-state partner two weeks before the election (February 18, 2020) or mailed them from their own state (all writers for the out-of-state condition lived outside of the target voter’s state) a couple days later (February 20, 2020). It is assumed that targets received postcards from approximately February 24-26, 2020. See original study blog for more details.

Two primaries – This study enrolled voters from competitive state legislative districts in Florida and Minnesota who were considered Democratic base voters (partisanship scores of 80+) but low-mid voter turnout propensity for primary elections (25-60). After pulling all voters who fit this criteria, we randomly selected 10,000 voters from each state’s list, and randomized each state’s list into the 2 conditions: control (no postcards) or postcards. This resulted in a sample size of 19,999. We recruited Sister District volunteers to write the GOTV postcards and mail them to an in-state partner approximately two weeks before each primary election (Florida on March 3, 2020 and August 4, 2020; Minnesota on February 18, 2020 and July 28, 2020). It is assumed that targets received postcards approximately a week before the election. See original study blog for more details.

Postcard Postmark – General Election Basic Takeaways:

- Receiving a postcard before the March primary had no effect on November general election voter turnout in the sample (p = 0.773).

- Further, there were no differences in the size or significance of the effect of the postcard for the in-state or out-of-state conditions (boths ps ~ 0.8).

- This data suggests that, though these postcards were effective in the primary season, their effects did not last until the general election. This was largely expected, but helps to underscore the fact that voter contact needs to be repeated and frequent because contact/messaging decays over time (Chong & Druckman, 2010; Hill et al., 2013).

- You can read more about this study here.

Two Primaries – General Election Basic Takeaways:

- Voters who received GOTV postcards ahead of the primaries did not have significantly higher odds of voting in the general election compared to controls (p = 0.219).

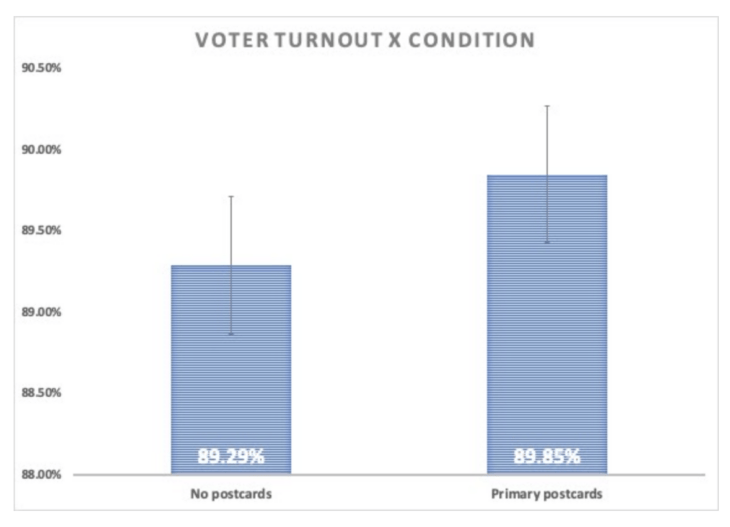

- Practically speaking, people who received postcards during the primary election season voted in the general at a rate that was 0.56% higher than control participants. But, as this difference was not statistically significant, this effect is simply suggestive and trending in the expected direction.

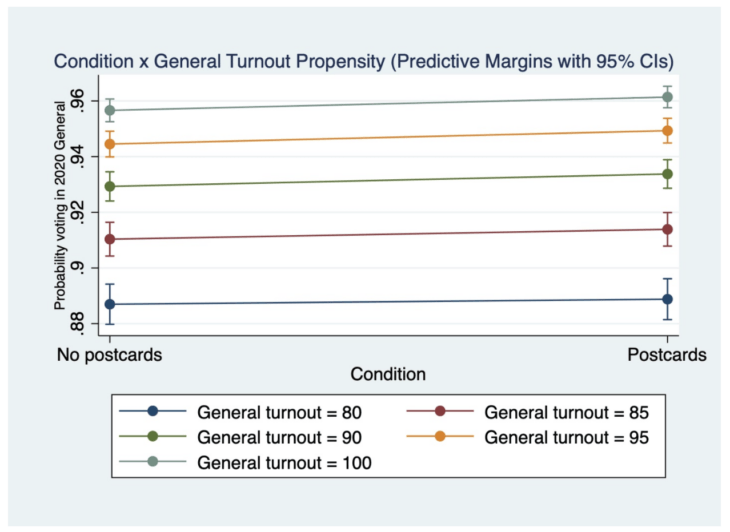

- An exploratory model also revealed a significant interaction effect (p = 0.035) between condition and general election turnout propensity score.

- When graphed, it appears that voters who received primary GOTV postcards had higher odds of voting in the general election when those voters had higher general election turnout propensity scores (80+). On the other hand, the interaction shows that voters who received primary GOTV postcards had lower odds of voting in the general election when those voters had lower general election turnout propensity scores (45 and lower).

Key findings from Two Primaries:

- People who received primary postcards in the original study voted at a slightly higher rate than control participants, but this difference was not statistically significant.

- Voters who received postcards during the primary elections turned out at a rate of 89.85%, while people who did not receive a primary postcards turned out to vote at a rate of 89.29%. This difference of 0.56% was not statistically significant (p = 0.219). This indicates that receiving primary postcards was associated with voting in the general election more, but it was not statistically meaningful in this sample.

- It is notable, however, that this effect is larger in magnitude than many of the effects SDAN observes in postcarding studies, which generally range from 0.2-0.3%.

- Voters who received postcards during the primary elections turned out at a rate of 89.85%, while people who did not receive a primary postcards turned out to vote at a rate of 89.29%. This difference of 0.56% was not statistically significant (p = 0.219). This indicates that receiving primary postcards was associated with voting in the general election more, but it was not statistically meaningful in this sample.

- Effects varied by general election turnout score, with voters with high general election turnout scores seeing a small boost in turnout and voters with lower general election turnout scores seeing a small backlash in turnout.

- This interaction was statistically significant (p = 0.035). This indicates that primary postcards had different general election influence depending on how likely people were to vote in the general election in the first place. This relationship is graphed below.

- This exploratory model provides evidence that postcards may behave differently for different groups of voters, especially when it comes to downstream effects from voter tactics.

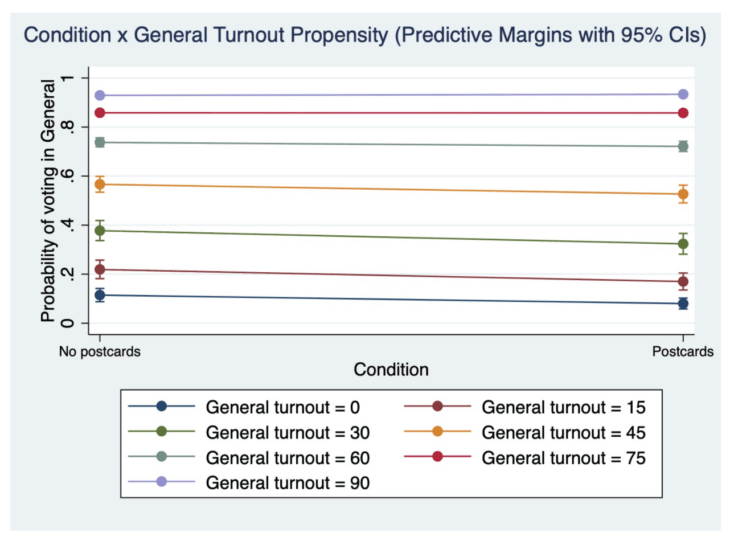

A second graph zooms in on the upper scores as their trend lines are hard to see in the graph above.

A second graph zooms in on the upper scores as their trend lines are hard to see in the graph above.

Caveats and considerations

- Both studies used a unique sample of voters. These studies targeted specific districts in a narrow range of states, and only voters with primary voter propensity scores of 25-60 and partisanship scores of 80+. This group of voters is not representative and limits the generalizability of these findings.

- This sample was targeted based on primary turnout scores. These are downstream analyses of studies conducted during the primaries, so the targets were considered low-mid propensity for primary elections. However, the median presidential general election voter propensity of both of these samples turned out to be over 90, indicating that these voters were no longer low-mid propensity voters, but rather base voters, when the general election came around.

- These analyses were not the original intentions of these studies. SDAN’s original studies attempted to influence primary voting turnout. We were curious, after their surprising efficacy, if their effects lasted into the general. However, these studies were not designed for that purpose, and all findings should be considered exploratory for that reason.

Contributions and Future Directions:

This analysis adds to the growing literature SDAN has produced on the efficacy of postcards. In the case of the postcard postmark study, there was no lasting effect. But in the case of the two primaries study, there appears to have been a lasting effect, that, though not significant in the entire sample, demonstrates how influential voter contact can be. Additionally, a statistically significant interaction revealed that the primary GOTV postcard tactic did boost general election turnout downstream among voters who were highly likely to vote, but did not boost turnout among voters who were unlikely to vote. This is a useful finding, because it suggests that this tactic should be used among some voters (high turnout) but perhaps not others.

Further, these analyses also demonstrate the cost effectiveness of postcarding during the primaries, as any downstream effects on voting would be considered a bonus.

The results of these studies continue to suggest that there are no real downsides and some possible real upsides to primary postcarding for people above 80 in modelled general election turnout scores. It may present more challenges for a lower turnout general election population (45 and lower), at least for downstream general election effects. More downstream analyses of primary tactics should be conducted in order to determine where these effects fall within the context of all voter tactics.

If you’re interested in reading more about this study, a longer report for the postcard postmark general election analysis is here and a longer report for the two primaries general election analysis is here.

SDAN’s commitment: It is SDAN’s intention to provide as much context as possible to allow for the nuanced interpretation of our data. SDAN’s convention is to contextualize effects by reporting p values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes for all models tested (these items may be in the longer report linked in the blog). Additionally, SDAN always differentiates between planned and exploratory analyses and a priori and post hoc tests, and reports the results of all planned analyses regardless of statistical significance. If you have questions about these findings please email Mallory.

A second graph zooms in on the upper scores as their trend lines are hard to see in the graph above.

A second graph zooms in on the upper scores as their trend lines are hard to see in the graph above.