Abstract: This study explored whether sending text messages reminding voters to return a requested absentee ballot could boost voter turnout in the 2020 general election in Georgia. A random sample of voters in Georgia who had Democratic support (partisanship) scores of 80+, had cell phone numbers in the voter file, and had requested absentee ballots but had not yet returned them as of the date of study intervention were enrolled in the study. A randomly chosen half of these voters received a text message reminder to return their absentee ballot on October 9, 2020, with information on how to do so, while half did not receive any communication. A randomly chosen subsample of the treatment subjects was enrolled in a substudy where they received an additional reminder text message on October 27, 2020 (results reported separately). The results indicate that the text message appears to have had a large effect in increasing voter turnout (p < 0.001). Further, when looking at how this varies based on how likely the voter was to turn out already, it appears that the text was particularly effective for people with lower predicted turnout scores (45 and below) compared to people with higher predicted turnout scores. These results suggest that text message chase is potentially a promising tactic to increase turnout, at least in the sample tested. There are some limitations of this study, discussed below.

Objective: This study explored whether chasing requested absentee ballots with a text message reminder to return them could increase voter turnout in Georgia.

Background: This work was conducted to address the efficacy of chasing absentee vote requests with text message reminders to return those ballots. Specifically, it tested the efficacy of sending a single text message reminder to people who had requested but not yet returned their ballots in increasing voting rates. The study assumes that people who requested absentee ballots are more likely to return them when encouraged and reminded to. Absentee ballot chase has largely been done in the area of direct mail by organizations like the Voter Participation Center (VPC). This study extends this tactic to text messages.

Specifics:

This study targeted voters who had requested but not yet returned an absentee ballot in Georgia as of the date of randomization, who had phone numbers listed in the TargetSmart voter file, and who had Democratic support (partisanship) scores of 80+. This yielded a total of 306,220 targets. These targets were randomized and 51,000 were randomly chosen for the sample and then randomly assigned to either the control condition (where voters received no text message) or the treatment condition (where voters received a text message reminder to vote by mail). Randomization and treatment (texts) occurred on October 9, 2020. A second message was sent to a subset of targets on October 27, 2020 (this substudy is controlled for in this analysis but reported separately). All participants were tracked through the voter file to determine if they voted in the 2020 general election and by which method.

Basic Takeaways:

- The regression model indicates that, when controlling for several other variables, receiving one text message reminder made people significantly more likely to vote (p < 0.001).

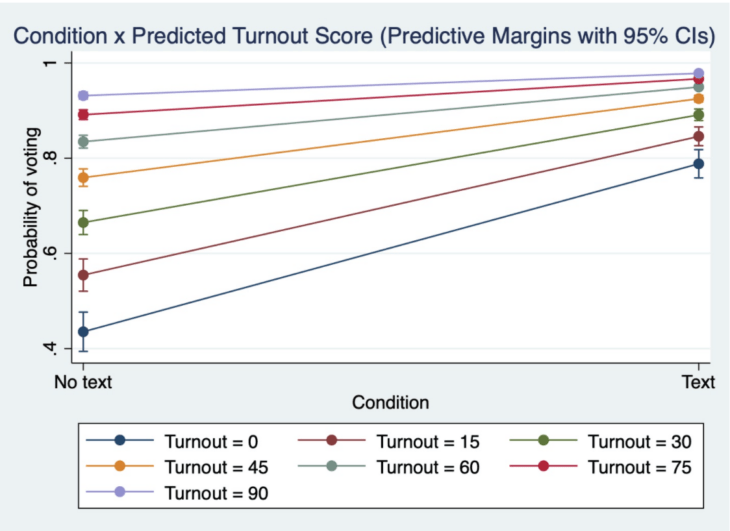

- The exploratory model (looking at whether modeled turnout score moderates the effect) indicates that this texting tactic is more effective for people with lower predicted turnout scores (p < 0.001) compared to people with higher turnout scores.

- It appears that people with predicted turnout scores up to 45 experience a boost in turnout from receiving a text message based on the graphed interaction. The effect appears to be much smaller with higher turnout scores.

- This data suggests that text message reminders for ballot chase may be an effective tactic for boosting turnout, especially for voters who are less likely to vote.

- Voters included in this study were targeted because they were Democratic leaning voters who lived in Georgia, had phone numbers listed in the voter file, and had already requested an absentee ballot. They also happened to have an incredibly high average modeled turnout likelihood (median of 97.3). This does not describe the average voter, so these results should not be widely generalized.

Key findings:

People who received a VBM text message did vote more than people who did not receive a VBM text message.

- According to the odds ratio for condition, people in the group that received the text message had 3.8x higher odds of voting than the group that did not receive a text message (p > 0.001). This indicates that people who received text messages voted more than controls who did not receive texts to a statistically meaningful degree.

- Please note that odds ratios are not the same as the practical difference in % turnout between conditions, they are a measure of the difference in odds of performing a specific behavior (in this case, voting) between the two groups (in this case, no text message vs text message).

An exploratory model testing whether texts worked differently based on how likely the voter was to turn out already (predicted voter turnout score) was also significant (p < 0.001). The graphed interaction indicates that people with low turnout scores were more affected than high turnout likelihood voters.

- Based on the graphed interaction below, it appears that all voters benefitted from receiving one message, but the effect was larger for people with lower turnout scores.

- However, more than 75% of the sample was in the 91-100 range. That means that this interaction should be replicated in a sample with more normally distributed turnout likelihood scores. This sample just ended up being an incredibly high turnout sample, with little room to improve their voter turnout, with both conditions voting at over 95%.

Caveats and considerations

- The study sample was unique. The inclusion criteria for this study, having a Democratic support score of 80+, having already requested an absentee ballot, and having not returned it yet, means that this sample of voters is not representative of the larger US electorate.

- The study sample had high likely turnout scores. The targets were chosen based on the inclusion criteria listed above, and predicted turnout likelihood was not included. However, the sample ended up being highly skewed towards high turnout voters, with a median turnout score of 97.3. They also voted at over 95% in both conditions, indicating this sample is very high turnout compared to the general population (voter turnout in Georgia last year was 66.1%.

- Another study was run during this study on the same people. We ran a substudy looking at the effect of two texts at the same time, on the same sample. We attempt to statistically control for substudy membership in our analysis, but it is inevitable that it had some influence on this study’s results as well. This tactic should be replicated on its own to determine its true efficacy.

Contributions and Future Directions:

This joins the Mississippi NAACP partnership GOTV texting study as the only text messaging voter mobilization studies SDAN has conducted, and is the only one of the two to have positive effects. It suggests that text message chase for VBM ballots may increase voting. This is especially positive news, as text messaging is relatively cheap and fast compared to other methods, which are either more costly or more time-consuming. Further, the exploratory findings suggest that lower turnout voters may be particularly affected, which may mean that this is a particularly good tactic for low turnout likelihood voters. If this finding can be replicated, it may make this tactic even more cost efficient, allowing people to target those who will be most affected.

Due to the unique nature of this sample, and the issues caused by the simultaneous substudy, this result should be replicated to ensure it is reliable. Further, turnout scores were so skewed in this study that another sample, perhaps with stratified sampling for turnout scores, should be used in a future study to determine if these effects replicate in a more normal distribution of turnout likelihood scores.

If you’re interested in reading more about this study, a longer report can be found here.

SDAN’s commitment: It is SDAN’s intention to provide as much context as possible to allow for the nuanced interpretation of our data. SDAN’s convention is to contextualize effects by reporting p values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes for all models tested (these items may be in the longer report linked in the blog). Additionally, SDAN always differentiates between planned and exploratory analyses and a priori and post hoc tests, and reports the results of all planned analyses regardless of statistical significance. If you have questions about these findings please email Mallory.