Gabrielle Goldstein, SDAN Director of Research;

Mallory Roman, SDAN Associate Director of Research

Objective: In January 2019, we surveyed our members to learn more about what motivates them to be part of our community, and what factors are associated with higher levels of participation in SDP activities.

Background: Trump’s election surprised some political experts and voters.(1) After the 2016 election, there was an uptick in political and civic engagement among certain segments of the population, reversing a 25 year trend of decline.(2, 3) Few systematic surveys of political volunteerism and activism have been done in the current political environment. An exception is a 2017 survey of March for Science protestors, which revealed that the current political administration contributed to their desire to march, along with a concern for the environment and a desire to highlight the importance of science.(4) This Sister District survey adds to this base of knowledge by investigating what motivates Sister District’s members to engage in political volunteering.

Specifics: Sister District Action Network (SDAN) surveyed the activist volunteer populations of Sister District Project and its sister organization, SDAN. The survey was designed to investigate volunteer engagement and satisfaction, and included various measures from psychological and political science. Analyses reported here looked at what combination of factors best predicts Sister District involvement (that is, participation in Sister District activities). 898 complete or mostly complete survey responses were analyzed.

Conclusions and Takeaways:

1. Team infrastructure matters.

Membership on one of our large established teams, which have the most developed infrastructure, is associated with higher levels of Sister District participation. In other words, the stronger your team, the more Sister District activities you do. Moving from a smaller, less established team status to a larger, more established team status is associated with a 5.17% increase in volunteer participation.

Takeaway: Teams should invest the time and resources to build their internal infrastructure, as this can be a powerful way to boost volunteer participation.

2. Relationships matter.

What we see driving higher levels of participation is not demographics, like age, race, and gender. Instead, it is things like whether volunteers feel invested in their team and whether they feel close to their team. Most of the variables that were significantly associated with participation were social in nature.

Takeaway: Teams should invest in relationship-building as a team, as this can be a way to boost volunteer participation. Get to know your volunteers, and build your community through social investment.

3. This isn’t (just) about Trump.

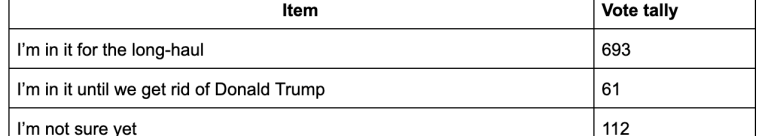

The overwhelming majority of respondents say they plan to be involved in political activism “for the long haul,” as opposed to just as long as Trump is in power. In other words, rather than being fueled by Trump-specific rage, the majority of respondents see their civic engagement as a long-term project, which doesn’t depend on the White House’s occupant. This finding challenges common narratives that folks on the left are only or mostly motivated to engage because of Trump.

Takeaway: Trump may have galvanized certain folks to get involved, but at least at Sister District, folks plan to stay and have strong motivating concerns beyond Trump, including gerrymandering and building a positive future.

Key Findings in More Detail

Factors that Predict Higher Levels of SDP Participation:

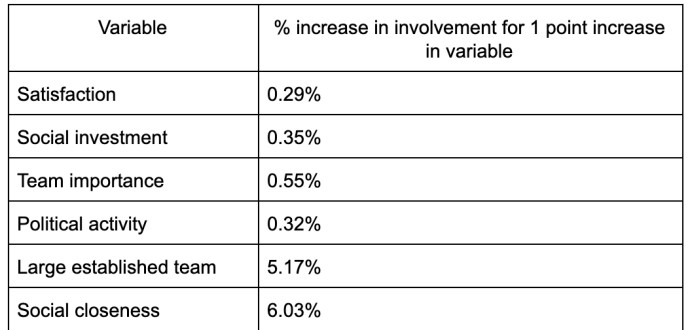

We found that certain factors independently statistically significantly predicted participation in SDP. These included*: satisfaction with SDP, social investment in SDP, the importance of the team aspect of SDP, current level of political activity, member status on a large established team, and interpersonal closeness with their team. *State of volunteer’s residence was also included in the model, but the value did not have a meaningful interpretation, and so is not in this writeup. Full regression results are cited in the full report.

*Involvement scores ranged from 0–35; Please note the ranges for each variable were measured on different scales, which affects the percentage estimates. For instance, large established team is a binary variable, which means a person can only increase 1 point on this variable, while a person can increase 54 points in political activity if they begin at the lowest score and end at the highest score. Please see the full report for more information on variable range.

However, it is important to note that our study design does not allow us to demonstrate whether these factors lead to increased participation in SDP or if they are simply related to higher levels of participation in SDP.

Factors that Do Not Predict Higher Levels of SDP Participation:

Interestingly, demographic factors like race, gender, age, marital status, education level, kids in the household, and even party affiliation were not significantly related to higher levels of participation in SDP. This suggests that aspects of the social/team situation like whether or not you feel close with your team have more to do with volunteer involvement than personal characteristics like age. This makes sense, because several personality psychology findings that indicate that people’s behavior varies quite a bit depending on the situation.5 Even though political involvement seems like a personal interest, the same social influences at work in our real lives appear to apply to participation in Sister District as well.

Factors like beliefs in political self-efficacy or previous political involvement, both factors that might be expected to relate to current political involvement, were also unrelated to a volunteer’s level of participation in SDP.

Additional Insight:

Even though Donald Trump was a big motivator for volunteerism, the vast majority of respondents said they were in it for the long haul. This indicates that our volunteers are not principally fueled by anger towards Trump, but rather have a longer time horizon for their civic engagement.

Study Limitations: The sample is not representative of the US population. In addition to being skewed in terms of gender and race (the majority of respondents were white women), the sample is also more educated than the general US population. Therefore, this survey provides interesting insight into SDP volunteers, but those insights may or may not be generalizable to the entire SDP volunteer base or to the entire US population.

Please donate to support our work at SDAN!

References

- Gelman, A., & Azari, J. (2017). 19 things we learned from the 2016 election. Statistics and Public Policy, 4(1), 1–10.

- Sánchez, D. M. (2018). Concientization among people in support and opposition of President Trump. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(1), 237–247.

- Skocpol, T. (2019). Making Sense of Citizen Mobilizations against the Trump Presidency. Perspectives on Politics, 17(2), 480–484.

- Ross, A. D., Struminger, R., Winking, J., & Wedemeyer-Strombel, K. R. (2018). Science as a public good: Findings from a survey of March for Science participants. Science Communication, 40(2), 228–245.

- Kammrath, L. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Mischel, W. (2005). Incorporating if… then… personality signatures in person perception: beyond the person-situation dichotomy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(4), 605.