Abstract: This study tested the efficacy of handwritten postcards that welcomed newly registered 18- and 19-year-old voters of color and gave them information about the upcoming election for increasing voter turnout. The postcards were sent to this group of Virginia registered voters ahead of the 2021 gubernatorial and state legislative general elections. In order to be included in the sample, targets had to be registered Virginia voters who were 18-19 years old at the time the list was amassed and were identified in the TargetSmart voter file as a race other than white. In the analysis, it does not appear that postcards influenced voting, and in fact, the direction trended away from the expected effect with controls voting more than postcard recipients (p = 0.724). There was no moderation effect of predicted turnout, suggesting that predicted turnout likelihood did not influence postcard efficacy (p = 0.604). Interestingly, there was a marginally significant moderation effect of modeled partisanship score on condition, such that people who were predicted to be more right-leaning responded better to the postcards than people who were modeled to be more left-leaning (p = 0.055). These initial results suggest that there was no main effect of postcarding, but the postcards may have been effective for specific groups of people, like more right-leaning people. As a small group of voters in this demographic living in Virginia, this is not a widely generalizable test. However, it does indicate that more research is needed to determine the best practices for reaching out to this specific group of registered voters.

Objective: This study aimed to explore whether sending handwritten welcome postcards emphasizing the identity of being a voter to newly eligible, recently registered non-white voters with information about the upcoming election could boost voter turnout in the 2021 Virginia general election.

Background: This study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that investigated the effects of sending welcome voter postcards on voter turnout. As less is known about young people with little to no voter history and little consumer history to inform their predicted scores in the voter file, including young people of color, many people in this demographic may be overlooked by traditional campaign targeting criteria.

Specifics: This study was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed by SDAN. It targeted registered Virginia voters who met the inclusion criteria: were 18 or 19 years old when the list was pulled on July 15, 2021, and were listed in the voter file as a race other than white.

A total of 16,989 targets met these criteria and were randomized into two conditions: The control condition, where voters did not receive any communication, and the treatment condition, where voters received a handwritten postcard shortly before the election (estimated arrival dates of October 22-October 27, 2021). After the election, data was matched back to TargetSmart’s voter file to determine if voters targeted in this study voted in the 2021 Virginia general election.

Basic Takeaways:

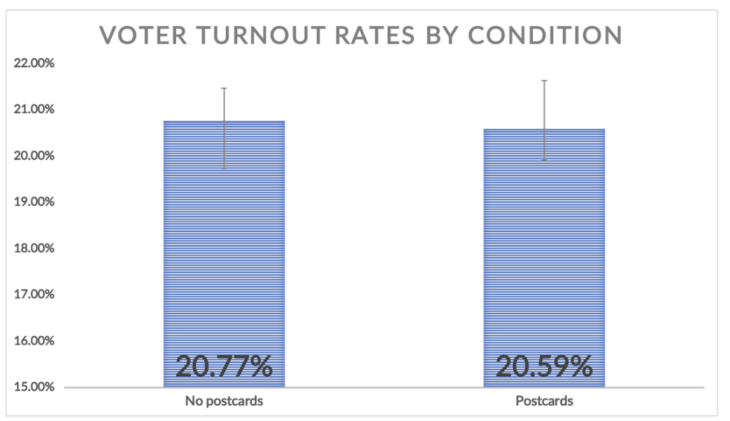

- People in the postcard condition voted at almost the same rate (20.59%) as those in the control condition, with control participants having a slightly higher turnout rate (20.77%). This difference in turnout was not statistically significant (p = 0.724).

- The efficacy of the postcards was unaffected by voter turnout propensity, an indicator of how likely voters were to vote already (p = 0.604).

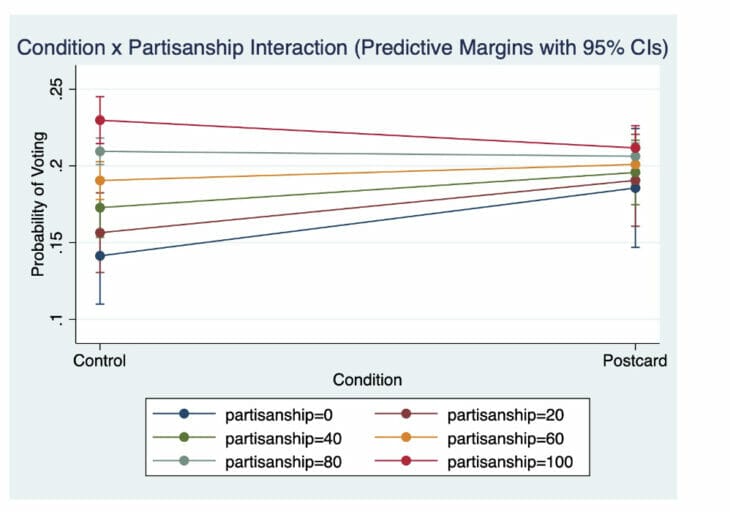

- The interaction between condition and modeled partisanship (how likely someone is to vote for Democrats) was marginally statistically significant (p =0.055). The interaction indicated that these postcards were more effective for voters with lower partisanship scores, or, in other words, those more likely to vote for Republicans.

- This study suggests that this tactic, in this particular sample, was ineffective in increasing voter turnout, with the postcard condition being statistically indistinguishable from the control condition.

- The narrow focus of this work, 18- and 19-year-old newly registered voters of color in Virginia, suggests that these findings cannot be widely generalized.

Key findings:

People who received postcards voted at about the same rate as people who did not receive postcards.

- Voter turnout was actually 0.18% higher in the control condition compared to the treatment condition. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.724). This means that the postcards appear to have effectively had no effect on influencing voter turnout in this sample.

The efficacy of the postcards was not affected by the targets’ predicted likelihood of voting in the general election.

- While some tactics seem to work better for people at higher or lower predicted turnout scores, we saw no effect, such that this tactic was ineffective for folks at all levels of predicted turnout (p = 0.604).

- However, it is important to note that we did not target folks based on their turnout scores, as we assumed that these scores would not be highly accurate for young, new voters. But these modeled turnout scores turned out to be significant predictors of voting for this sample.

Targets who were more likely to vote Republican appear to have responded better to the postcards in this sample.

-

- Results suggest that people with higher partisanship scores, or those who are predicted to be more likely to vote for Democratic candidates (those with scores over 50%), may have reacted more negatively to the postcards. But people with lower partisanship scores, or those who are predicted to be more likely to vote for Republican candidates (those with scores under 50%), appear to have reacted more positively (p = 0.055).

- We are unsure how accurate these predictive scores are in this young sample due to limited data. Further, the mean partisanship score in this study was 78.2, with a median of 83.2, indicating that a minority of people in the sample had low partisanship scores.

Caveats and Considerations

- Generalizability is limited. This study was meant to engage an understudied and underserved population of the electorate, newly eligible, recently registered voters of color. While the sample includes all Virginia voters who met these criteria, it was still fewer than 20,000 people, indicating that these findings apply to a relatively small group of people.

- We are underpowered to detect some effects. Due to the very small sample size and the small size of the difference between the groups, we were severely underpowered to detect statistically significant effects in this sample. However, it is important to note that we could not have increased power by increasing the sample size, as all Virginia voters who met the criteria were enrolled in this study. This indicates that attempting this approach in a larger sample may not be useful without additional alterations to the method.

- Restricting the population makes it challenging to see race effects. Though we wanted to focus on young, newly registered voters of color specifically as an under-targeted population, the absence of targets in the sample identified as white in the voter file makes it difficult to determine if this tactic works differently on people of color, or differently on people from specific racial groups.

- Predicted scores may not be reliable. Predictive scores in the voter file often include information about voters from their past voting histories and their consumer activities. There is simply more data to base these predictions on for people who have longer voter and consumer histories than the new adults in this sample.

Contributions and Future Directions:

These results largely indicate that the postcards in this study did not affect voter turnout. This efficacy was not affected by predicted voter turnout likelihood but was somewhat affected by partisanship. This trend revealed that people with lower partisanship scores, or those more likely to vote for Republicans, were more influenced by the postcard than people who were more likely to vote for Democrats.

The study has various limitations, including the fact that it targets a narrow range of Virginia voters. In addition, it seems likely that some predictive scores for this young group of voters are not as accurate as they are for older voters, making the partisanship interaction difficult to interpret. We are also severely statistically underpowered.

While it is important to appeal to this group of voters and attempt to mobilize them for elections, this does not appear to be an effective tactic for doing so. Among other reasons why this may be so, it is possible that a number of our targets simply never saw our postcards. Many 18- and 19-year-olds are registered to vote at their parents’ houses and may not have seen postcards sent there, particularly if they were no longer living at home, including at college. This ‘welcome to being a voter’ tactic may be more effective via text messages that are more likely to be sent directly to the intended recipient.

A longer report can be found here if you are interested in learning more about this study.

SDAN’s commitment: It is SDAN’s intention to provide as much context as possible to allow for the nuanced interpretation of our data. SDAN’s convention is to contextualize effects by reporting p values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes for all models tested (these items may be in the longer report linked in the blog). Additionally, SDAN always differentiates between planned and exploratory analyses and a priori and post hoc tests, and reports the results of all planned analyses regardless of statistical significance. If you have questions about these findings, please email Mallory.