The term ‘identity politics’ is often used to refer to the encouragement of political action related to specific demographic groups one is a part of, like women, or a racial/ethnic minority. While the term is frequently used dismissively, its critics are missing one crucial thing: our identities meaningfully shape our experiences, our thoughts, and our feelings when it comes to the world around us. How could they not inform our political interests?

This is something political actors and strategists know well, and they often try to use it to their advantage. From political speeches to policy platforms, political insiders know that you must appeal to different demographic groups in an authentic way in order to win votes and influence voters. This has spawned endless think-pieces on activating young voters, voters of color, digital natives (Ohme, 2019), etc.

In this blog we will discuss the social psychological underpinnings of identity, and how appeals to identity are used in a variety of political contexts.

What is identity?

Identity is a sense of self that is heavily influenced by the social networks one is a part of, and the larger world that those social networks are embedded in (Howard, 2000; Stets & Burke, 2000). When we think about who we are as people, we often start with descriptive adjectives, like we are kind, thoughtful, or snarky. But fairly quickly, we start getting into the social parts of our identities. These include groups one belongs to like generation, gender, citizen or resident of a specific place, member of a specific family, worker in a specific trade, and so on.

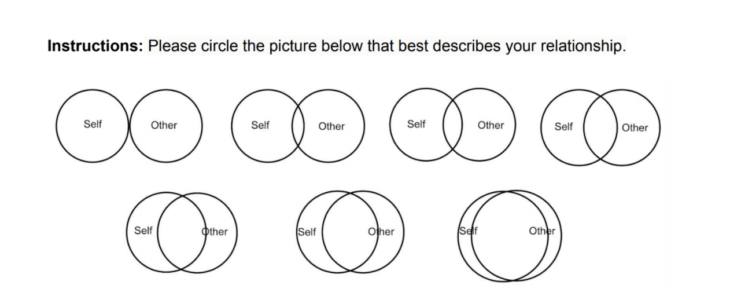

It turns out that much of our identity as individuals is wrapped up in our relationships with other people or groups of people. This is so common that there is actually a famous scale in social psychology that measures how much we include other people in our conceptions of ourselves using increasingly overlapping circles (Aron, Aron, & Smollan). We may share no overlap in identity between ourselves and strangers (top left of the figure below), but we may include our parents, siblings, children, close friends, etc in our ideas about our “selves” in meaningful and significant ways (bottom row of the figure below).

The inclusion of the other in the self (IOS) scale. Image taken from this University of Washington document.

You’re in or you’re out

The overlapping circles in the figure above might as well represent the overlap we share with others in terms of our ingroups. Ingroups are just groups of which you are a member. They are our families, our neighborhoods, our cities, our states, our interest groups, our friend groups, our race, our gender, our schools, and so on. The ingroups we are a part of heavily shape our identities. We include our ingroups in thoughts of who we are (Tropp & Wright, 2001). And we include them in the way we view ourselves in relation to people who belong to groups we aren’t members of, otherwise known as outgroups (Brewer, 1979).

It’s unsurprising that we are generally proud members of groups we choose to belong to, but research has shown that people can also form group allegiances very quickly, even in situations where people are randomly assigned to groups that should have little meaning. In the Robbers Cave experiment (conducted in 1953), researchers randomly assigned 11 year old boys at a summer camp to two groups (Sherif, 1961). The experimenters encouraged both bonding within the groups, and competition with the other group, and found that the boys formed very strong bonds with their assigned group and very strong attitudes of hostility towards the boys in the other group (Sherif, 1961).

This was a fascinating finding, as it demonstrates that even superficial group memberships can still invoke powerful loyalty. This idea was further solidified in research using a method called the minimal group paradigm, which suggests that all that is required for ingroup loyalty and outgroup bias to form is being a member of the ingroup (Tajfel et al., 1971). Identity is heavily informed by our group memberships, but this research demonstrates how quickly those memberships can be established.

How is it used in politics?

Party line voting

The major political parties attempt to foster a sense of identity around “being a Democrat” or “being a Republican” in hopes that political beliefs will become internalized as a significant part of our “selves.” Promoting party line voting sets folks up to vote along party lines for all offices, and frames voting split-ticket not just as a choice of candidate, but as an action that is inconsistent with who people are on a basic level (see this example from the Trump campaign in 2018 that encourages voters to “vote Republican”). Since the US is an increasingly politically polarized nation, this influence that political allegiance has on identity for a large portion of the population may contribute to the decline in split ticket voting that we see in the US.

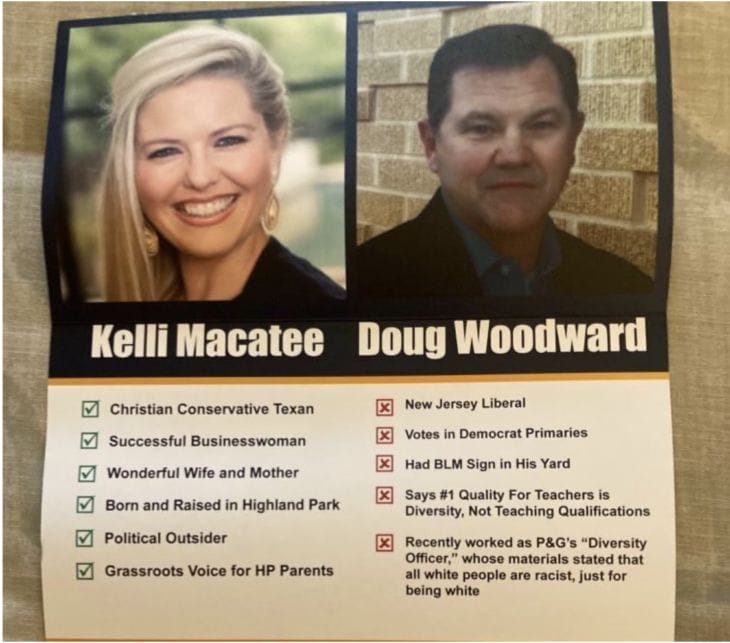

Ingroup bias

Politicians, similarly to political parties, often try to invoke ingroup bias in their rhetoric. For the reasons stated above, it is easy to play into the animosity between political groups, which in turn, can very clearly align the politician and the group of voters they are appealing to as members of the same ingroup: the group of people who belong to this party, and definitely not that one. The mailer for a 2021 school board race below very clearly lays out the candidate’s ingroups that she thinks will appeal to voters, and highlights her opponent’s comparative outgroup status.

Be a voter

This common political phrasing is used to invoke the desirable identity of being a voter as opposed to just asking folks to engage in the desirable behavior of voting (Bryan et al., 2011). The idea is that if we internalize ‘being a voter’ as part of our identity that we are proud of, we will behave consistently with it by voting. This ad from Vote Save America not only uses ‘be a voter’ language, but it suggests that being a voter will help save America.

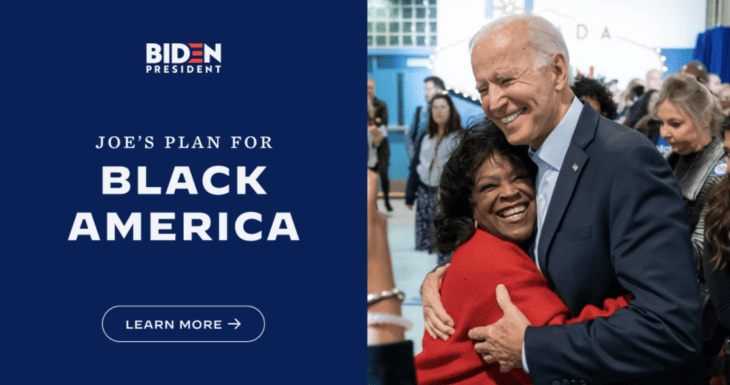

Policy

Every election, politicians release policy platforms and take policy positions that speak to specific groups, partially with the hope that these stances will be appealing to those groups, and thus garner more votes from said groups. Examples of this are support for things like the Equal Rights Amendment, civil rights legislation, reproductive rights legislation, LGBTQIA+ legislation, and immigration reform. These policies may appeal more to voters that legislation would directly affect if enacted.

Conspiracy theories

Unfortunately, identity can be used to keep people engaged in communities that advocate political conspiracy theories. Groups like Q-anon are minimal groups in the sense that they are groups composed of people who share a set of beliefs and an internet forum. But these beliefs and forums can come to engage people so powerfully that their identities are heavily invested in being a follower of that group. Followers then form communities around the conspiracy, often to the detriment of other important relationships. We have seen this same pattern with other groups that align around identity, like the KKK, the Proud Boys, the tea party.

Intersectionality

We’ve discussed the ways in which people have multiple identities, but we haven’t discussed the idea of intersectionality. The idea is that our multiple identities overlap and interact in such a way that they shape our experiences through the compounding of privileges or disadvantages conveyed by those identities (Crenshaw, 1989). The political idea of intersectionality is that policy that targets specific interest groups almost never reflects the experiences of all people who occupy that group, because within each group we have people who occupy all sorts of other identities that may be associated with outgroups. We all come to the table with a variety of demographic characteristics that convey societal or structural associations that mean that our experiences are not the same, even if we do occupy some of the same ingroups. The concept of intersectionality from an activism standpoint is that policy must be reflective of ALL members of a group the policy is made to protect (e.g., women includes women of all races, abilities, economic statuses, immigration statuses, etc), or it is inherently not intersectional policy (Hankivsky & Cormier, 2011). Our overlapping identities mean that harm that comes to anyone is harm to an ingroup member in some way, because we are all human, and our rights and freedoms depend on one another.

Our “selves” are complex, ever-changing, and highly informed by our social connections. They inform our daily behavior and our beliefs, so it is important to be a critical consumer of political information that invokes identity. It’s a natural tendency to align with our ingroups, but it’s often our outgroups that help to influence our political beliefs in a more equitable direction and open our eyes up to problems we are not personally experiencing.

References:

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596.

Brewer, M. B. (1979). In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 307.

Bryan, C. J., Walton, G. M., Rogers, T., & Dweck, C. S. (2011). Motivating voter turnout by invoking the self. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(31), 12653-12656.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. U. Chi. Legal f., 139.

Hankivsky, O., & Cormier, R. (2011). Intersectionality and public policy: Some lessons from existing models. Political Research Quarterly, 64(1), 217-229.

Howard, J. A. (2000). Social psychology of identities. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 367-393.

Ohme, J. (2019). When digital natives enter the electorate: Political social media use among first-time voters and its effects on campaign participation. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 16(2), 119-136.

Sherif, M. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robbers Cave experiment (Vol. 10, pp. 150-198). Norman, OK: University Book Exchange.

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 224-237.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149-178.

Tropp, Linda R., and Stephen C. Wright. “Ingroup identification as the inclusion of ingroup in the self.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27.5 (2001): 585-600.